Winter Nomads

Carole and Pascal embark on their winter transhumance with three donkeys, four dogs and eight hundred sheep, braving the cold and the snow, with a canvas cover and animal skins as their only shelter at night. An adventure film at the heart of a territory undergoing a radical transformation.

Synopsis

Pascal, 53, and Carole, 28, are shepherds. In the month of November 2010, they embark on their long winter transhumance: four months during which they will have to cover 600 km in the Swiss-French region, accompanied by three donkeys, four dogs and a eight hundred sheep.

An exceptional adventure is about to begin: they brave the cold and the bad weather day in day out, with a canvas cover and animal skins as their only shelter at night. This saga reveals a tough and exacting profession requiring constant improvisation and unflinching attention to nature, the animals and the cosmos.

An odyssey through a region undergoing profound changes that render this kind of expedition more difficult every year, particularly when the grass for the sheep has to be found between villas, railroad track s and industrial areas.

An eventful journey with surprise encounters, moving reunions with farmer friends, nostalgic figures of country life that is shrinking away fast.

A film dominated by the strong personalities of Pascal and Carole, whose relationshi p and joie de vivre transform this transhumance into a magnificent hymn to freedom, at opposite extremes of our comfortable reality.

Winter Nomads is an adventure film, a contemporary road movie, a reflection of our current world, which takes us back to our roots and our inner questions .

More about the film

On the film website www.hivernomade.ch

Carole, the sheperdess

Carole Noblanc, 28, from Brittany, France, grew up in Quimper where she worked as a dietician... until the day she met Pascal, six years ago, during a hike in the Swiss Alps. She is the only woman in Switzerland and maybe in Europe to experience the winter transhumance. She knows it and feels justly proud. This young woman of character, comfortable with herself, who grabs life with both hands, decided to learn a trade that was a far cry from the urban culture she grew up in: command ing dogs, packing donkeys, setting up camp, caring for the sheep. A difficult life choice, far from sedentary comforts, which she shouldered with panache.

What circumstances brought you, a dietician from Brittany, to the Swiss countryside to learn how to look after eight hundred sheep?

I always wanted to leave my native Brittany, where I was living in Quimper town centre, surrounded by cars and cinemas, but I didn't want to leave without having some goal. I have long been a lover of spending time in the mountains, and it was when I was on holiday in Switzerland that I met Pascal, who was a shepherd in an Alpine pasture. He offered me a job and I passed my two-week trial period, so that I decided to drop everything in Brittany. One month later, I moved to Switzerland. In the Alps, I started off making pancakes, – Breton pancakes, naturally – and I discovered transhumance the following winter.

How many transhumances have you followed?

The first year, I couldn't see myself spending the whole winter outside! So I got a job in a bistro, again making pancakes, but I often went to visit Pascal. I soon realised that I definitely preferred transhumance to making pancakes! The following year, I followed it more regularly. In all, I have been on six journeys, including two from start to finish.

What are the hardest aspects of the shepherd's work to master?

You need to be alert to what's going on the whole time. It is also very difficult to give orders to the dogs. I think my voice is not strong enough to assert myself and the high-pitched sounds are less audible for dogs. With Titus, whom I've known since he was a puppy, it was OK, but not with the others. You really need to have your own dogs. Finding the right grass for the sheep is also very complex. You have to go and scout out the land while the sheep are ruminating, around noon, and avoid the grasslands which have been soiled with slurry and are unfit for animal consumption. The worst thing is the railway. One day I found myself with the flock split in two by a passing train. Luckily no sheep were killed!

In the film, we often see you in front of the flock giving the sheep dry bread. Why is that?

They are the bellwethers, that is, the five or six sheep that we keep from year to year to lead the flock. We give them names – Irmate, Tabasco, Marilyn –, we give them a bell and we spoil them with dry bread and chocolate. They are part of the family like the donkeys and the dogs. When the other sheep hear the tinkling, they do what they have always done: they follow!

We often hear it said that life on the transhumance is very hard for a woman. More so than for a man?

The problem is physical strength, but some women are as tough as men. I'm not up to pulling the tent ropes, or tightening the straps which hold the donkey packs. You also have to put up with taking just one shower a week, but hygiene conditions can be just as irksome for a man as for a woman!

How do you explain the fascination that transhumance has for the population?

People are surprised that transhumance is still practised and that you can go without modern comfort. Above all I think it is the choice of living outside society, at nature's pace, and escaping from the vicious circle of "working in order to pay" which is their dream.

Do you appreciate the amount of visitors drawn by the transhumance?

Not always! After spending all day in the cold, I sometimes just wanted a bit of peace; so I found it difficult to socialise around the fireplace with people who came to share our meal and then went off to sleep in a warm bed.

Have you had to deal with hostility from farmers?

Some of them are very happy to see us come and it all goes smoothly, but others have the idea that it is their place and they can't stand the idea of sheep eating their grass. I sometimes had the impression that they were envious watching us going on our way with our animals.

During transhumance, what is your perception of sedentary life?

During transhumance, I appreciate the spirit of freedom and sedentary life seems limited to me.

What are your thoughts when you see the land being covered in concrete and the reduction of farming and forage areas?

Luckily there are still the mountains, because there is less and less room for nature in the plains.

Do you like wearing the traditional wool clothing of the Bergamo shepherds?

You have to wear wool around the fireside, because the cinders make holes in synthetic clothes. In the forest, clothes get rough treatment and only wool can really stand up to it. We also wear capes which protect us from the cold very well.

At Christmas, we see you enjoying oysters and a roll cake. Do you miss the sea?

No, but I miss the taste of it! That's why I get brought some oysters at Christmas for a treat.

In Winter Nomads, you are always seen with a book within reach. What did you read?

Marie Laberge's trilogy Le goût du bonheur (Gabrielle, Adélaïde, Florent), The Best Village in the World by Arto Paasilinna and Barbara Kingsolver's Prodigal Summer.

What did you like most about nomadic life?

I loved being surrounded by nature with the sheep, the donkeys and the dogs and waking up every morning in the middle of the forest in a different landscape each time. It is a great privilege to have been able to live in these surroundings for all those years.

Apart from the influx of visitors, what did you least like?

I was very scared of storms in the forest, with the ever-present risk of a branch or a tree falling on top of me.

Did you agree without hesitation to be filmed by the Winter Nomads film crew?

When Manuel von Stürler talked about his project, we never thought it would take off the way it did! The shoot went well, in a climate of trust and mutual understanding and I really enjoyed the good meals they cooked up for us. It was a real pleasure!

This year, you have decided not to follow the transhumance. Do you have other projects in mind?

I need to find a bit of solitude after years of having too much social life in the transhumance and the mountains. Obviously I often think back to this wonderful adventure, but I have other projects right now: travelling and making soap to sell in markets.

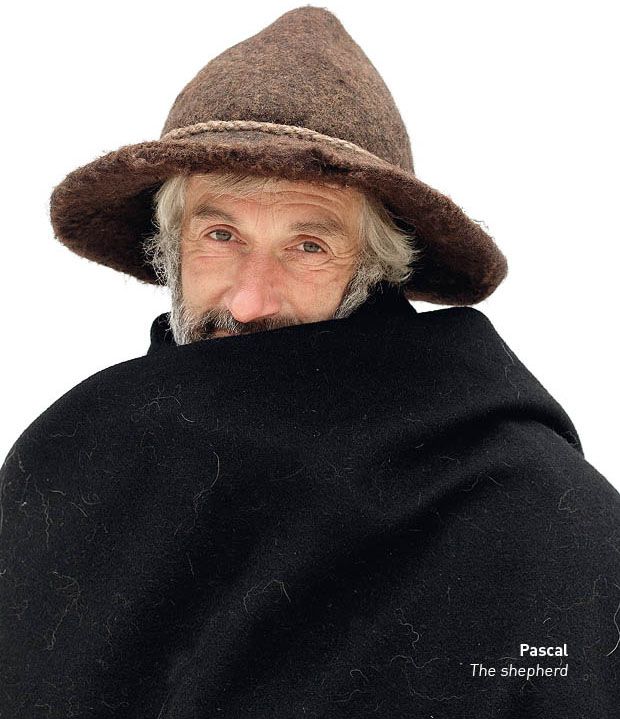

Pascal, the sheperd

Pascal Eguisier, 54, was born in Corrèze, France, to parents with an industrial background. Growing up in the countryside, he discovered the world of cattle breeding through his classmates and was happy to lend a hand in the cowsheds, where he learned how to care for the animals.

After a year spent in the Pyrenees as an assistant shepherd, he went to Switzerland the following year to do a summer pasture with 350 sheep. This is where he made a decisive encounter: with shepherd Louis Gabbud who was about to embark on his 56th winter transhumance. Fascinated by his personality and his way of life, Pascal got himself taken on as an assistant shepherd by Bergamask shepherds (northern Italy) and trained for three years in what was to become his profession and his reason for living.

He then settled in Switzerland, where he has worked as a winter transhumance shepherd for 33 years.

We discover you in Winter Nomads skilfully leading a herd of eight hundred sheep: you seem to have been predestined to become a shepherd. Is this the case?

I come from a family with an industrial background. My mother was a Latin and Greek teacher. Naturally, with a name like Pascal I seem to have been predestined for this work... How did it all begin? I'm the first to be surprised. I must have an innate love for the Earth and especially for animals. I come from the Limousin in France, a region with a high percentage of cattle, and I could have chosen cattle breeding as a profession, but I ultimately devoted myself to sheep. Even when I was very young I helped a calf-breeding friend with the hay or the cleaning of the cowsheds whenever I had a moment.

How long have you been a shepherd?

I did a summer season in the Pyrenees and then came to Switzerland, where I've been working for thirty-three years. I first looked after a herd of sheep belonging to a clinic in Montreux which raises mountain sheep for cell therapy purposes very much appreciated by men and women in high places!

Can the profession of shepherd be termed an occupation or a vocation?

To live with a herd of sheep round the clock for four months, the term priesthood is surely more appropriate! A shepherd's work can be compared to the connection linking a monk to his monastery.

What does one think of, alone in the forest at night surrounded by sheep?

I don't know if it's always a good idea to think, but one thing's for sure: there is communion with all the elements, the sky, the wind, the snow, the rain... This is when I have the feeling to be a son of the Earth.

What aspects of transhumance do you appreciate least?

I like everything about transhumance, but rain and storms a little less. It affects the herd and me too, particularly at night when I want to sleep. There is nothing more disagreeable for the body than changes in climate and all-pervading humidity. I prefer cold winters and snow, provided it doesn't prevent the sheep from grazing. This is why I've been cherishing the dream of joining the Nenets in Siberia beyond the Arctic Circle to follow a transhumance of reindeer. Dry cold doesn't bother me in the least, even below 40° C. I've already met keepers of reindeer in southern Siberia. The wide open spaces and the authentic environment are conducive to a different form of transhumance.

After how many years does one become an experienced "conductor" of a herd of sheep?

To find a balance and not to give in to stress, you need quite a few years of experience. When you're a second shepherd, you just follow the movement, but when it comes down to taking over the lead, that's something else. In the beginning, you panic because you don't know how to lead a herd. There are decisions to take and if they prove wrong, my employer won't be satisfied with my services.

Carole, your second shepherd in Hiver nomade, is still learning the craft. How is she doing?

Carole, who is my companion, is very courageous. I take my hat off to her and I have a lot of praise for her. To share one's life with a gruff, explosive and fiery individual like me isn't easy! Fortunately, she's got character too, but she has sometimes had to put up with my mood swings as regards the handling of the herd.

How do you explain the fascination transhumance holds for the population?

People's curiosity about transhumance sometimes gives us the impression of being museum pieces! This attraction is understandable, though. Seeing a herd of sheep revives the connection with the Earth in some and evokes a biblical theme to others. No doubt, this vision reminds them of their aspiration for a more authentic and meaningful life, but can they renounce material security and superficiality? I've chosen freedom, I travel light, I own nothing and I have no banker breathing down my neck. My greatest wealth is living in nature, waking up in the morning and beholding the sky and the Moon. It's a magnificent palace not even kings are entitled to!

How many curious and enthusiast people approach you on average?

If it rains, if it's foggy or if it's cold, there's not a soul. There aren't that many courageous people after all...

Have you already been chased off a field by farmers who are hostile to transhumance?

Oh yes! It's very rare, though, because after all, we only pass through. The majority of farmers are happy to see you come back year after year and some of them have become acquaintances.

Does the cementing of farm and crop land hinder you?

Yes, but evolution is a feature of any society. Fortunately, the new villas are mostly built around the villages and not dispersed in the countryside. That's already a positive point. However, is it really necessary to cement agricultural paths? I wonder.

You have adopted the tradition of the Bergamask shepherds - woollen clothing, large hats, travelling with donkeys - whereas you could move in 4-wheel-drive cars and wear synthetic clothes. Why this choice?

I was extraordinarily lucky in being able to learn from the Bergamasks - who have ancestral knowledge and know-how - how to dress in wool. This living material obtained from the sheep is perfectly adapted to the life of a shepherd, but it's increasingly difficult to find.

Do the donkeys and the dogs belong to you?

My boss provides the donkeys, but the dogs and the equipment are mine. The dogs accompany me all year round. It would be impossible to lead the herd without them.

What is a shepherd's pay for a transhumance?

For an enthusiastic shepherd who lives in conditions that are not always easy, money is not what counts!

What do you do during the eight months between two transhumances?

I keep cattle on an Alpine pasture and I travel.

Did you hesitate before accepting a film crew's presence in the transhumance?

I accepted because Manuel von Stürler is a good friend, but also and above all for my children, who are 23, 19 and 8 years old, respectively, and whom I see only little. They will be able to know their father through these images. It's a kind of transmission.

What do you expect from the release of Winter Nomads?

That the film may contribute to people's understanding of transhumant shepherds who have, over time, perpetuated one of the oldest occupations in the world. And that it may help me to establish contacts in Siberia to be part of a transhumance with reindeer!

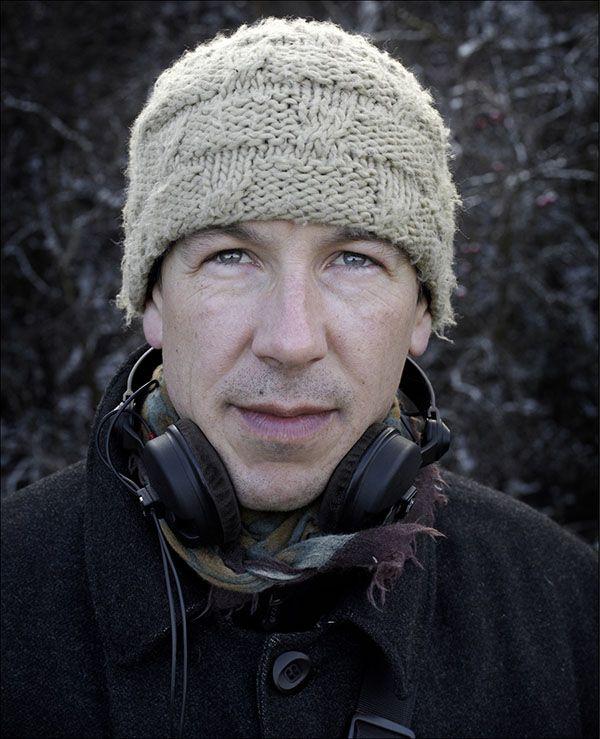

Manuel Von Stürler, le réalisateur

Born 1968 in Lausanne, Swiss and French national.

After having studied the trombone at the Music Academy of Neuchâtel and at the Jazz and Contemporary Music School in Lausanne, Manuel von Sturler performs live a wide repertory, from classical to jazz and contemporary music.

He plays regularly with artists such as the Philippe Lang Group, Malcolm Braff, Leon Francioli, Stéphane Blok.

He composes music scores for theatre and stage performances. Together with Arthur Besson, he founds the DUO MATò Company with the aim to focus on the music as a central element in the narrative and artistic process of a theatrical play.

Their approach has brought to them stage directors such as Dominique Bourquin, Denis Maillefer and Fabrice Gorgerat.

The fact of exploring such various artistic fields includes also the aim of discovering the world. He did so, together with his companion and their two children, totalizing two years of nomadic journeys, in the Middle East, Persia, Eastern Europe, Iceland, Bolivia, Chile and Patagonia.

It gave him the opportunity to rediscover and practice an other of his passion: photography. He made several films on a personal level before being commissioned as a professional to direct his first corporate film for a major company, Securitas.

In 2008, he starts his feature documentary project Winter Nomads. World premiere at the 62nd Berlinale 2012 (Forum).

Before directing Winter nomads, your first film, you were a musician and a composer for stage and theatre. Why and how did you turn towards filmmaking?

Towards the age of 20, after my studies of music, I was confronted with the dilemma of choosing between my first passion, music, and my developing passion for photography and cinema. I finally opted for a career in music, all the while continuing amateur photography and video. My encounter with transhumance inspired me afresh and triggered the imperious desire to dedicate myself to a different field of creation.

The nomadic life of the Roma has often been treated in movies, but that of shepherds perpetuating the ancient tradition of transhumance much less. How did this topic impose itself on you?

After a long trip with my family to the other side of the planet, I heard that an impressive flock of sheep had passed in front of my house which is located on the outskirts of an urban area. So the following winter, I was on the look-out for them. I eventually found them near a small town nearby. I experienced the same sensations as during my long trip.

Thanks to the shepherds I rediscovered my region and was beginning to see the groups of villas encroaching on the countryside in a different light. It was an incredible encounter: first of all with the extraordinary spectacle of the passing sheep, but particularly with the shepherds, Pascal and Carole. This transhumance adventure captivated me. It was an eye-opener as regards the transformation of the countryside and the "los-angelisation" of the Swiss countryside. The idea of making a film was immediately obvious.

Is transhumance, a remnant of olden times, well considered in the countryside?

The biblical symbol of the shepherd, just like the return to nature and the Epinal image (traditionalist depiction) that transhumance represents hold an astoundingly powerful fascination. Wherever they go, shepherds attract interest and sympathy. In fact, they are so much in demand that they sometimes hide in a clearing so as not to be disturbed! Shepherds and their flocks are, however, not always welcome: some farmers, fearing for their crops, are on the defensive for all sorts of reasons and prohibit access to their land. Transhumance is regulated by the authorities who assign certain areas to the owners of the flocks, but the farmers are under no obligation to accept the sheep on their land.

How were you received by the shepherds?

We got on immediately. Despite his gruff exterior, I found alert-eyed Pascal instantly charming. Carole too. They have a taste for beauty and "pure" things; they have neither jeep nor do they wear synthetic, garish colours. Instead, they have opted for donkeys and the beautiful traditional clothes of the shepherds from the Bergamo region. I got involved in their adventure very quickly. I wanted to go back the next day and the day after.

Were you able to easily convince Pascal and Carole to participate in the shoot?

They were on their guard at first. It has to be said that they are very frequently photographed and that there are two amateur videos about them. When they realized that my project was more ambitious and that I was determined, they took me seriously. During the development phase of the project, which took nearly two years, I participated in a complete transhumance, the time required to establish mutual trust.

You highlight the shepherds' know-how, their ability to guide the flock toward "authorised" pastures and to ensure the health of their animals. Were you impressed by their skill?

This is a very exacting profession and I wanted to show its complexity, its suspenseful reality as well as the movement of the flock. Shepherds are constantly on the alert and the moments of respite are rare. Guiding a flock of eight hundred sheep along a path that is three metres wide and lined with planted fields that no sheep may trample on is not within the capacity of just anybody. It requires the nimble fingers and the skill of a conductor!

Reading is a shepherd's only form of entertainment. What do they read in the light of their frontal lamps?

Carole always had a book in her pocket which she opened every time they were having a rest. She was reading, for example, Cantique de l'apocalypse joyeuse, by Arto Paasilinna.

What distance did the shepherds and their sheep cover during the four months of transhumance?

About 600 km, i.e. an average of 5 km a day.

The shepherds travel with three donkeys, eight hundred sheep and four dogs. They spend every night on the edge of the woods, in the cold of the winter. How did the crew adapt to these particularly difficult conditions?

The crew was formed according to the goals I had set myself and to the specific conditions imposed by the transhumance. The director of photography, Camille Cottagnoud, is accustomed to filming in the mountains and my brother, Marc von Stürler, who is also used to this kind of conditions, recorded the sound. We obviously needed to adapt to the pace of the transhumance, not the reverse!

The soundtrack of the film leaves little room for music. What reason made you focus on direct sound?

I wanted to highlight the beautiful, natural sounds of the transhumance and was considering not using any music at all. In the end, I did feel the need to include some music to punctuate the film with different phrasings, to mark temporality and to take a little distance.

Although you are a composer yourself, you entrusted Olivia Pedroli with the task of writing the music. Why didn't you write it yourself?

Film directing is very demanding and I didn't have the time necessary to devote myself to composing the music. Plus the fact that I thought it would be interesting to have a different point of view and different ears contributing to the narration.

To elaborate the scenario, you chose to cooperate with Claude Muret, who has already backed up several filmmakers. Was his contribution productive?

Although I have been engaged in various creative processes for over 20 years, I quickly understood that I needed the experience of a "wise man" to help me. In this respect, Claude Muret played a decisive part. He was very present at each stage of the process.

Did your inexperience in cinema present a handicap in finding a producer?

Before approaching any producers, I had worked a lot and had already put together a strong crew. So I didn't exactly knock on doors empty-handed! Heinz Dill and Elisabeth Garbar were immediately enthusiastic. They were also the first ones to evaluate the potential of my film and to have confidence in me.

After this first successful film, do you have any other film projects?

Yes, I have several documentary projects going, but it is essential to get the right "feel" that allows you to carry through a long-term project with conviction.

Tags: agriculture, documentary